In 2016, we provided a grant to Torth Y Tir for a new pizza oven as part of the A Team Challenge. Needless to say, they’ve ‘risen’ a bit since then. Recently, a collaboration with Jason Taylor at The Source Image has seen their story beautifully encapsulated in film.

What is Peasant Bread?

Peasant bread is a loaf that is baked with the skill of a craftsman, the love of an artist, and the storytelling of a writer.

In the past, peasant bread was made with what was available to the farmers who were considered poor. These farmers managed the whole process of growing wheat, milling flour, and baking bread.

Although the modernisation of the food system since developed, in France, baking bread in a similar vein continued and formed the tradition of ‘paysan boulanger’.

Today, the old values - where nutritious food comes directly from harmony with the Earth - makes peasant bread a true symbol of food sovereignty.

Peasant bread makes use of whole flour to produce a rustic and hearty loaf. There is a stiffness to the crust and the texture of the crumb is coarser compared to bread baked from refined flours. These unique and natural inconsistencies remind us that real bread is something authentic, sensual, baked with intention, and a gastronomic delight. The true beauty is in the taste – the notable full-bodied, almost nutty, flavour originates from the health of the soil.

“Whereas bread had become something that is problematic to our health we want to restore it to something that’s actually good for us and good for our communities.”

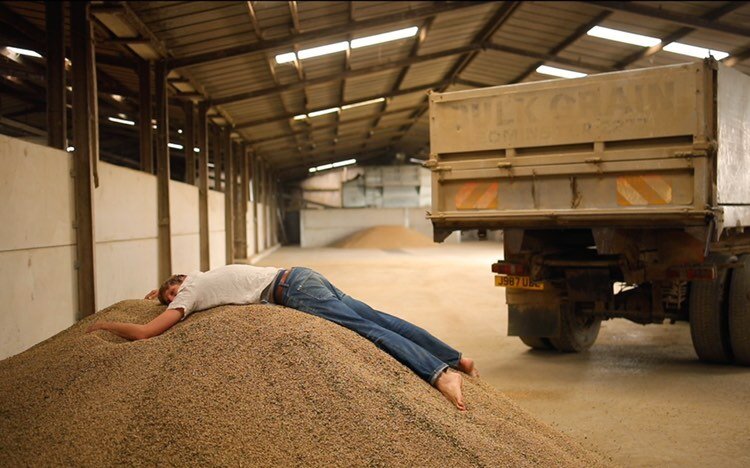

Image courtesy of Torth Y Tir

WhAT IS Heritage Grain?

The future of farming requires us to farm in accordance to the natural ecosystems. Heritage Grains are a useful tool in the toolbox for feeding the world whilst farming regeneratively.

Heritage grains were bred, grown, harvested, and milled at a time when artificial inputs and machinery were mere imagination.

For a sustainable future, they already have a head start. They are regionally adapted to our climate. As Rupert says in the video, they out compete natural weeds, whilst the in-field diversity allows for a natural ecosystem where predator pest species can live. Also, through adapting to local regions, they even possess their own natural defences to some native insects.

But above all else, they taste really good.

If you’d like to read more on the future of wheat, this blog post by the Sustainable Food Trust is a good place to begin. So too this Wicked Leeks article ‘Grains to Change’. There is also an annual gathering of the UK Grain Lab, which brings together not just farmers and bakers, but also millers, breeders, scientists and academics, hosted by the Small Food Bakery in Nottingham.

From Field to Loaf

What makes Peasant Bread so important is the journey from field to loaf.

In the soil, live a universe of microorganisms that support the health of the plant, ecosystem, climate, and us! The health of the soil matters greatly to the health of the biosphere, for carbon sequestration, water cycling, and nutrition.

One of the best ways to grow healthy soil is through the diversity of plant species – different root systems use and cycle different nutrients at different times. Therefore, a diversity of available nutrients supports plant health without the need of inputs. Having a mixed population of wheat in the field really is more nutritious. An example of a good ‘field-to-loaf’ flour that is available to buy is the YQ wheat produced by Wakelyns.

Peasant Bakers generally farm their grains at small scale and therefore, require either a sympathetic miller or ownership of the equipment to mill the grain into flour. For Rupert, he owns a unique piece of milling machinery that is designed to produce beautiful flour sensitively (after all, this is an art).

The allure of the loaf really materialises during the baking process. With ‘the artist’s loving hand’ the dough is fermented, risen into a leaven, mixed, folded and risen again ready to bake.

“This is a moment of alchemy; the final stages of the transformation from the field to your loaf, when raw ingredients become larger than the sum of their parts through the magic of a multitude of microorganisms as they unlock nutrition, develop flavour and cause the dough to rise.”

Who is Torth Y Tir?

Who knew that locally grown wheat would survive in the very wet, west Wales? Well, according to historical records it has been as natural for as long as people ate bread.

Peasant Bread and heritage grains are farmed, milled, and baked in St Davids, Pembrokeshire by Torth Y Tir (Welsh, meaning Loaf of the Land) - a Community Benefit Society, owned and run by their members, who all hail from the local community.

Their aims are:

To practice and promote community-supported baking and heritage cereal production in a spirit of solidarity and openness.

To widen access to artisan, sourdough bread and the skills needed to produce it.

To demonstrate and teach the benefits of growing, processing, stone milling and baking heritage grains through the principles of agroecology and handmade, naturally leavened, wood-fired bread.

““Your loaf starts in our field. Nourished by the sun, the rain and the soil, our heritage grains are then freshly stone-milled on-site before being naturally leavened and baked entirely by hand in our wood-fired oven. It’s a process of dedication and a dance of time and intention”. Rupert Dunn ”

All photos copyright of Jason Taylor, The Source Image